|

A story and teaching notes by

Dr. Marvin Bartel, Ed.D.

"How

old

are you?" "Four and three-quarters." Ella like every child

her age was anxious to be five years old.

Ella and Grandpa were sitting together on the floor next to a low

bench. On one end of the bench Grandpa had placed a potted orchid

with seven blossoms. He had brought some paper and a soft lead

drawing pencil. Ella and Grandpa were eating cookies. Ella

had some milk and grandpa had some coffee. They were drinking from cups

Grandpa had made in his pottery shop. Ella liked to sit on the floor.

Grandpa thought it was okay, but it was sort of hard to get up.

Ella's grandfather often thinks about how young children learn.

Thirty years ago he had done his graduate work in art education.

He knew the research, the assumptions about the developmental stages,

and thinking styles of young children. Grandpa knew that many children

become stymied in their drawing ability because adults drew for them

rather than helping them learn to draw. Few adults understand how

to teach drawing to a young child.

Grandpa knew that young children draw without any instruction.

But, he also knew that many young children had become uninterested in

drawing or afraid to draw because "helpful" adults had discouraged

their natural inclinations to draw and learn from the practice.

Adults often draw for children and expect the children to imitate their

drawings. This seldom works. Young children make very inferior

copies. Both the child and adult give up in frustration. They excuse

themselves - assuming that drawing is a talent rather than a way of

thinking and seeing that is developed through practice.Well

meaning adults who expect imitation are expecting exactly the wrong

thing. The right thing is for the child to attend to her/his own

experience with the thing being drawn. Learning to attend to an adult's

drawing distracts from the learning task and produces dependency and

limits brain development. Drawing

is not an innate talent - it is a skill of the brain that is nurtured

through practice in attending to the thing being drawn - not an adult's

drawing of it.

Art educators find that most children

stop drawing entirely as they reach age eight or ten. By this age

they have become aware of how "stupid" and "childish" their drawings

look. These

"baby talk" drawings are too embarrassing. Grandpa thinks that if

we taught reading and writing as poorly as we teach drawing, about 10

or 20 percent the adult population would be literate.

Grandpa shares this story as insight

into how we need to change the way drawing is taught to

children. Please continue reading.

"I'm

glad you helped Grandma make these cookies. Aren't they good?"

"Yes!" Ella replied.

Grandpa

continued, "This is really

a beautiful orchid. I noticed yesterday that you were giving it some

water. How long have you had this orchid?" "Since I was born." Ella replied. "Wow, that's

amazing. When I get an orchid, it blooms for a few months, then

the leaves start to get yellow and pretty soon we just have to toss it

out."

"Who

takes care of this orchid to keep it so nice?" "Just me. I water it." Ella replied.

"Do you water it every day?" "No." "How do you know

when to water it?" "When the dirt feels dry." "Well, the orchid must

really like it. It sure has lots of flowers." "How many flowers

does it have?" Ella begins

pointing to each flower while saying

the numbers from one to seven. Grandpa exclaims, "Wow,

seven

blossoms!"

Grandpa

continued to talk about the orchid to get Ella to see more parts of

it. "Did you notice these silly roots? This orchid

has a

whole bunch of roots that are up in air. I thought just the

branches and leaves were supposed to be in the air. Why do you

think it has roots in the air?" "I don't know" Ella responds. Grandpa says,

"I don't know either, but I think the roots really

look

sort of funny."

Grandpa

continues, "Shall we see if you can draw a picture of just one

these

roots. You pick one of the roots that you like and I will teach

you how you can learn to draw it. Which root looks interesting or

silly to you." Ella points to

a root that is about 5 inches long

that arches up from the plant and then goes horizontally for two inches

and dips down again.

Ella

is anxious to start drawing and picks up her pencil. Grandpa

says, "Just a minute, I want to look at this silly root before

you draw

it. Watch my finger how it slides along the top of the root

slowly from one end to the other. Could you slide your finger

along the root and see how the line first sort of slants up. Then

which way does it go?" Ella

says, "It turns a little and still

goes up." "That's

right!" says Grandpa.

"Then which way does it go?" Ella

says,

"Then it tips a little bit." "Okay! That's right"

responds Grandpa.

Next

grandpa says, "Now I will go back a little ways and just point

to

the

root with my pencil, but I am too far away to actually touch the

root. Now watch me move the pencil in the air while I pretend to

slowly

draw the root in the air." Ella

watches. Grandpa says, "Now

you can slowly draw with your pencil in the air to practice making the

shape of the root." Ella

practices it by pointing her pencil to

the root and draws it in the air. Grandpa watches and says,

"That was good! Now practice it in air one more time, but this

time do it

really slowly so your pencil can follow the shape easier." Ella practices

again. Grandpa says, "I bet you could show me on the paper

how

root is shaped. Where do think the root should start so it fits

on the paper? Ella points out a spot on the paper and

Grandpa says, Good,

now you can draw it on the paper. While

you are drawing, you can stop and practice in the air anytime you are

wondering how to draw the next thing. Just stop drawing and look

back at the orchid and it will show you how it looks."

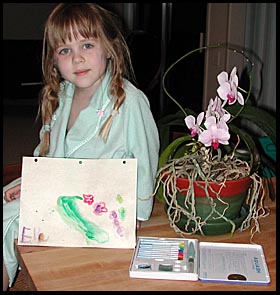

Ella,

age four and three quarters, proceeds to draw the root, the leaves,

the sweeping blossom stock and the 7 orchids and buds more or less from

observation. Grandpa sits in amazement and wonders if he will be able

to get up from the floor.

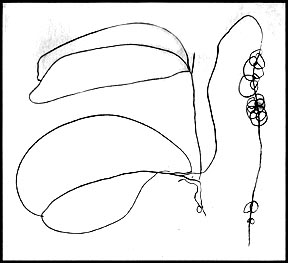

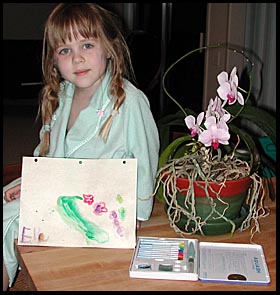

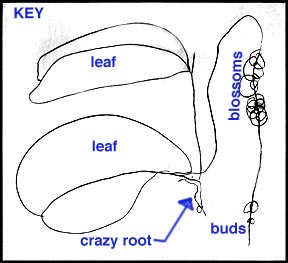

Ella's pencil

drawing of an orchid.

The original is

about 8 inches

wide.

Click here for her watercolor painting of the same plant.

Sequence: The

single root was first. Then the

bottom leaf and the top leaf. Thirdly, she added the blossom stem. The

blossoms and the buds were last. When you watch children draw flowers,

what do they draw first? How much to they add?

Postscript

Why do you think I zeroed in on the silly root rather than the orchid

flower? I assume that every child's brain already has a picture of a

flower ready to draw. This is an obstacle when teaching perception. The

part of our brain that learns how to make careful observations does not

develop if draw from what our brain thinks

that it already knows about how things look. New observations are

blocked or overlooked because of

these preconceptions. I look for subject matter that the brain has not

yet stereotyped and cataloged. Therefore, I often select the mundane,

the trivial, the little details, from the child's ordinary experiences.

When I talk about this to adults, I say that in order to learn to draw

we have to see the world without prejudice - as God sees.

PRINCIPLES

TO

SELECT SUBJECTS

When teaching perception, it easier if we select subjects that are new

and unfamiliar

(not yet learned). That is why the root and not the flower was used. A

familiar thing like a well loved toy animal can be made to look

unfamiliar by turning it upside down, backwards, etc.

When teaching

perception it is important to select something that is easy enough

to avoid frustration. That is why only one root was selected in this

story. Had Ella stopped after the one root, that would

have been fine.

It must be challenging

enough require some detailed study and concentrated practice in the air.

Using both touch

and vision is more perceptual than using only vision. That is why a

simple square thing, or a simple round thing like a ball, is not very

useful.

The thing observed has to be unexpected

enough in some way so that careful looking is required. Avoid

things for which the

child's brain has already created and stored a stereotyped image.

When teaching perception it is

helpful to select subjects that are emotionally important to the person

doing the drawing.

SHARING

SECRETS

When I teach I ask children if they can guess why I picked the subject

that

was picked. I explain the above principles to children so they can use

the principles themselves when they practice.

--see more below

|

|

How

to Draw

A

Poem

by

David

Wright

First,

grow

one;

fuss

with the soil;

search

for ample light.

Recall

the one

you

watered to death.

Learn

the name

of

the crazy roots,

(besides

crazy roots).

Trace

a single rhizome

from

node to soil.

Then

again. Again.

With

index finger,

sketch

it in the air.

Forget

Van Gogh.

Ignore

O’ Keefe.

This

is your flower,

its

curve, its day

to

bloom. Find

the

color then

close

your eyes

Wait

long enough.

You’ll know. Then,

you’ll

start to draw.

David Wright

© 2003

|

|

back to top of page ^

back

to top of page ^

Teaching

Notes

As the teacher, I did no drawing

in this drawing lesson. I draw the line on this. When the teacher

begins to draw, the child will stop looking at the real source and

begin looking at the adults replica of the source. This is not

learning to see. This develops a common problem among children.

We call it learned helplessness.

Ella

had no chance to copy my drawing. Ella had to get her visual data

from the orchid root itself. She was learning to be

self-sufficient - not dependent and helpless.

I showed observation methods. I never corrected Ella and took every

opportunity to affirm and encourage her efforts. Young children

respond positively to positive motivation. Negative motivation

may work to stop something, but it does not work to promote something

positive.

In subsequent lessons I have shown Ella how to use a "blinder" on her

pencil. A blinder

is an 8 x 8 inch piece of heavy paper with a small hole in the

middle. Her pencil is placed in the hole. The blinder hides

her paper while she draws a new thing. This keeps her eyes on the

subject instead of the paper. At age six when Ella wants to draw

a new thing she puts the blinder on her pencil and makes practice

drawings on her paper. Often this ends up to be a jumble of

lines, but the individual lines are amazingly faithful to their

sources. After this "seeing practice" she takes the blinder off

her pencil and makes another drawing while looking at her paper and at

the subject.

At age six, Ella

reads well and enjoys leaning to add two digit numbers.

Teachers are good at teaching reading, writing, math, and so on.

However, most children have no art teachers that bother to teach them

art. Too often their art is mainly offered as relaxation. Some

teachers give them busywork projects. The busywork is made up of

prescribed pictures, tracing, or craft projects that are largely pre

designed. Other teachers simply allow them play around and do

whatever they wish. If I were to choose, I would rather see the

'play around' method than the 'cute craft project' busywork. While

these activities are not immediately harmful, they do leave a gap in

their education and mental development.

In many schools art is taught so poorly in the younger years that most

children feel totally incompetent by the time they reach grade

three. Only the few who have practiced more excel. Often

the 'talented' ones have parents who are particularly generous with

materials and encouragement. These children are called the

'talented artists' in the class. The remainder of the class

suffer from what is called a "crisis of confidence". They stop

practicing because nobody ever helped them learn how to trust their own

perception and practice productively.

Schools in Japan are faulted by some because their culture honors the

group more than we do at the expense of the individual. Children

that are particularly gifted and creative are discouraged from being

different. "If the nail sticks out, hit it down." is a common saying.

This has both positive and negative educational and societal

outcomes. While individual creativity may suffer, the ability to

create and produce high quality in groups may be stronger.

Japanese schools include regular observation drawing along with work

from memory and imagination in the early school years. Young

children can often be seen in the school flower garden making

observation watercolor paintings or out in a plaza painting a fire

truck that is placed for their observation. They all learn to

draw as an expected part of the curriculum. While we tend to give

about an hour per week to art instruction, they are apt to allow about

three hours per week in the early grades. They develop extended

attention spans and the ability to focus on a task that serves them

well in other learning as well. -- more below

back to top

of page ^

|

|

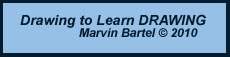

On

the following day after Ella did the pencil drawing at four and

three-quarters, feeling confident in her ability and self-sufficient,

Ella decided that she would try out a set of watercolors that her great

grandmother, age 94, brought her from Japan.

|

back to

top of page ^

|

SHOULD ALL THEIR DRAWING BE FROM OBSERVATION?

No. In addition to direct observations, other

good sources of content for children's drawings include, their imaginations

(another important area of brain development), their everyday experiences,

their memories, and special events (both good and

bad) in their lives (important for emotional development). We

motivate children to elaborate more more in their drawings by asking

them open questions that bring to mind ideas from their own experiences

- not by drawing for them. We

give positive feedback about their work. We provide unlimited paper or

a white board (with non-toxic markers). We treat the artwork as a gift

no matter how it looks. When we fail to understand we do not say,

"What is it?" We say, "Can you tell me more about this?" Young children

are not corrected in their drawing. If young children are corrected in

their drawing, they will automatically move to a less beneficial

activity such as watching cartoons on TV, or some other brain shrinking

activity.

Similarly

beneficial

activities include playing with simple blocks, Legos

(without patterns to follow), clay, Play-Doh, and so on. Blank

paper is better than coloring books (even coloring books can promote

learned helplessness). Coloring you own picture is better.

Drawing your own maze is better than doing somebody else's maze in an

activity book

Marvin Bartel Home Page

Goshen College Art Department

Goshen College

All

rights reserved. Photographs,

text, and design © Marvin Bartel and bartelart.com.

How

to Draw and Orchid (poem) is © David Wright

2003. Ella's work is

her property and may not be published without permission from her

parents.

Parents,

care-givers, pre-school teachers, and art

teachers may make one copy for personal study. Permission

is required to make any other copies, to publish, or to post on another

web site.

Please mention the URL or

the

title of this page in your correspondence with the author.

You may make a

link to this page from your page without permission, but you may

not

post this page or any photos from this page on another web

page without permission. Your

correspondence, experiences, ideas, and questions are welcome.

|